Scruggs, Metcalfe and Boyer

In the early 1880s three St. Louis residents would enter the life of William Seward Burroughs and make it possible for Burroughs to realize his dream and obtain a significant financial reward. Let's meet them and learn a little of their backgrounds.

R. M. Scruggs - The Merchant

Richard

Mitchell Scruggs was about four years older than Burroughs' father. He

was born in Bedford County, Virginia, in 1822. Richard was the second

son of Reaves Scott Scruggs who fathered 12 children by his first wife,

Mildred, and

two more by his second wife, Sophia. Reaves Scruggs was an influential

planter and politician of Bedford county. The principle route of

commerce in the area at that time was the Salem-Lynchburg Turnpike that

extended about fifty miles between those towns with Bedford, then known as

Liberty, lying halfway between them. At the western end of the

turnpike, Salem was the dominant town. Nearby Roanoke would come to

prominence much later in the 1800's.

Richard

Mitchell Scruggs was about four years older than Burroughs' father. He

was born in Bedford County, Virginia, in 1822. Richard was the second

son of Reaves Scott Scruggs who fathered 12 children by his first wife,

Mildred, and

two more by his second wife, Sophia. Reaves Scruggs was an influential

planter and politician of Bedford county. The principle route of

commerce in the area at that time was the Salem-Lynchburg Turnpike that

extended about fifty miles between those towns with Bedford, then known as

Liberty, lying halfway between them. At the western end of the

turnpike, Salem was the dominant town. Nearby Roanoke would come to

prominence much later in the 1800's.

At age 15, Richard went to work in a dry goods store in Lynchburg, Va., at the eastern end of the turnpike, and quickly rose through the ranks to become book-keeper and confidential clerk to one of the owners.

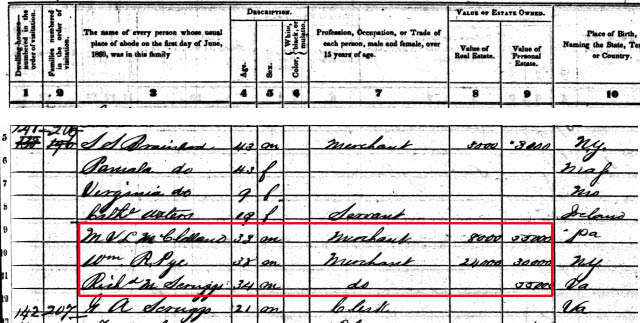

At age 25, Scruggs set out for New Orleans, intending to find a new job. He stopped along the way to visit a brother who had settled in Huntsville, Alabama and decided to take a job there at the branch office of a large New Orleans Cotton House. Scruggs soon became well acquainted with M. V. L. McClelland, the nephew of a very successful Huntsville merchant. Soon, McClelland and Scruggs were being encouraged to pick a city and start their own dry goods business there. McClelland's uncle proposed setting them up in either Montgomery, Memphis or St. Louis.

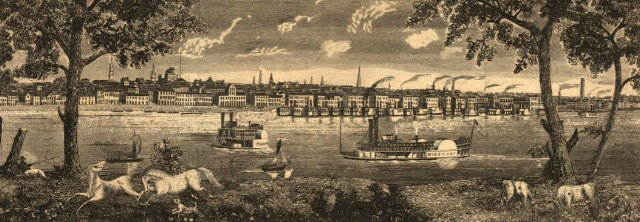

When Scruggs and McClelland visited St. Louis in May of 1849, they found a boom town that was a major gateway to America's westward migration. In 1850, the population of the city was about 50,000 and the city extended to the west only from the Mississippi river to Eighteenth Street. Church steeples were the tallest objects in town.

In March of 1850, the two young retailers opened their doors as McClelland, Scruggs & Co. The firm achieved an early and unique reputation for quality merchandise and grew rapidly along with the city. Around 1860, Scruggs withdrew from the company which passed into the hands of W. L. Vandervoort & Co. Throughout the 1860's a number of changes occurred as the Civil War ensued and by 1868, McClelland had retired, William Pye had entered the firm and Scruggs was now at the head of the firm of Scruggs, Vandervoort & Barney Dry Goods Company. The company would operate under that name for nearly a hundred years.

The original location of the Scruggs, Vandervort and Barney store was the southwest corner of Fourth and St. Charles where it stood until moving to a new location on the southwest corner of Broadway and Locust in 1888. The store moved to its final and better known location at Ninth and Olive in 1907. When an application was filed for National Historic Register status for one of the firm's warehouse buildings in 1984, the application noted:

Despite the setbacks of the Civil War and the financial panic of 1893, the firm moved into the twentieth century with a reputation for fine goods, integrity, service, courtesy and quality rather than for bargain prices. Their patrons included the wealthy elite of the city, and the dry goods store was often linked with cultural and charitable events.

In 1860, Scruggs was living a few blocks away from his business with his fellow merchants and his brother, Gustav. Each of the merchants had already accumulated a sizeable fortune for the day of around $60,000.

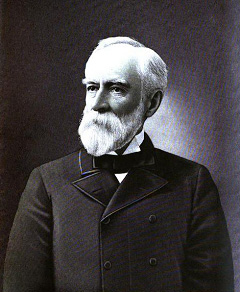

Scruggs would become a prominent and well-respected member of the St. Louis community. He became very well known for his philantropy, charitable work and as a churchman. The entry for R.M. Scruggs in the Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis, published in 1899 runs on for almost six pages, much of it devoted to his charitable works. As one example, the Methodist community of St. Louis built a new Cook Avenue Church in 1884-5. Of the $70,000 involved, Scruggs contributed $40,000. In about 1880, Richard and his younger brother, Gustav built a 7,000 square foot mansion in what was then nearly a rural area at 3617 Olive.

When Scruggs died in 1904, he left an estate valued at two million dollars. He

never married and the estate passed to various charities, both in St. Louis

and Virginia, but with the mansion going to Gustav. Gustav was the

number eleven child of Reaves Scruggs by his first wife. In 1881,

Gustav, at age 42, had suffered a severe fall and became an invalid.

He remained in the property on Olive along with at least two other Scruggs

siblings until the 1920s. When Gustav died, the property passed to

John M. Scruggs, Reaves thirteenth child and the oldest by his second wife.

John M. Scruggs had remained in Virginia and lived in Salem, at the western

end of that Salem-Lynchburg Turnpike.

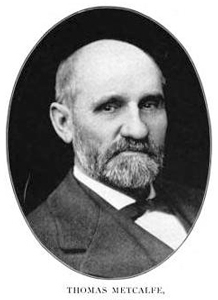

Thomas Metcalfe - The Lawyer

Thomas Metcalfe was born in Kentucky

on January

21st of 1838 making him nineteen years older than Burroughs. He was the son of William Melville Metcalfe and Amanda

McIntire Metcalfe both of Kentucky. William Melville Metcalfe, in

turn, was the son of Thomas "Stonehammer" Metcalfe, who served as the tenth

governor of Kentucky from 1828 to 1832. Governor Metcalfe and son

William lived near Carlisle, Kentucky, about 30 miles to the northwest of

Louisville. Both are buried there at "Forest Retreat," the governor's

farmhouse home.

Thomas Metcalfe was born in Kentucky

on January

21st of 1838 making him nineteen years older than Burroughs. He was the son of William Melville Metcalfe and Amanda

McIntire Metcalfe both of Kentucky. William Melville Metcalfe, in

turn, was the son of Thomas "Stonehammer" Metcalfe, who served as the tenth

governor of Kentucky from 1828 to 1832. Governor Metcalfe and son

William lived near Carlisle, Kentucky, about 30 miles to the northwest of

Louisville. Both are buried there at "Forest Retreat," the governor's

farmhouse home.

William and Amanda were not responsible for raising the young Thomas Metcalfe. At the age of three, Thomas was taken to live with Amanda's childless sister, Malvina and her husband, John Newton Congleton about twenty miles away in Mount Sterling. The Congletons reportedly helped out with the education of two dozen of their nieces and nephews.

Thomas Metcalfe taught school for a while after graduation and then decided to take up the law as a profession. He studied with local lawyers and eventually became a judge of the City Court in Mount Sterling. Along the way, he met and married Mary Chiles, daughter of Colonel Walter Chiles, a citizen of Mount Sterling and prominent Kenucky criminal lawyer.

Judge Metcalfe, as he would continue to be known, and Mary had three children while living in Mount Sterling. Their first child was a daughter Carrie, born in 1865. They had twin sons, Walter C. and Melville L. Metcalfe, born in 1867. Later they would have four more children: Landon, Thomas, Mary and Alice.

Metcalfe took his law practice and family to Atchison, Kansas, in 1869 where he practiced law with Senator Jno. J. Ingalls. He moved on to St. Louis in 1876. Some Burroughs' biographies mention Metcalfe as a member of the Scruggs, Vandervoort & Barney Dry Goods Company but there doesn't appear to be any evidence to support this. Metcalfe is found in the St. Louis city directories as either a partner or an individual practicioner from 1876 on. Metcalfe and family moved to the suburb of Webster Groves about eleven miles southwest of downtown in 1884. Another attorney living in Webster Groves and practicing downtown was John D. Gibson. City directories don't show evidence of a partnership between Metcalfe and Gibson but Gibson's son, Tom, has stated that they were law partners and both are listed at the address of 509 Olive as are four other lawyers.

An 1885 publication listing various St. Louis businesses describes the firm of Ten Broek and Jones which specializes in collection of mercantile claims and adjustments. It notes that the firm has twenty employees and has handled thirty thousand cases. The description notes, "That distinguished practitioner, Judge Thomas Metcalfe, is retained by them as counsel." It is certainly possible that Scruggs and Metcalfe became acquainted through work done by this firm or that Metcalfe was retained directly by Scruggs for collection work.

Joseph Boyer - The Entreprenuer

Joseph

Boyer was born in rural Pickering, Ontario, about fifteen miles northeast of

Toronto, Canada in 1848 making him nine years older than Burroughs.

His parents were farmers although he claimed his father had a greater

interest in working with and maintaining farm tools than actual farming.

At the age of eighteen, he found work as a mechanic's apprentice at the

large Hall Works in nearby Oshawa, Ontario. After three years there,

Boyer decided to head south and then west moving to San Francisco where he

quickly found work in a bay area machine shop. After a few weeks

there, Boyer and the shop parted ways.

Joseph

Boyer was born in rural Pickering, Ontario, about fifteen miles northeast of

Toronto, Canada in 1848 making him nine years older than Burroughs.

His parents were farmers although he claimed his father had a greater

interest in working with and maintaining farm tools than actual farming.

At the age of eighteen, he found work as a mechanic's apprentice at the

large Hall Works in nearby Oshawa, Ontario. After three years there,

Boyer decided to head south and then west moving to San Francisco where he

quickly found work in a bay area machine shop. After a few weeks

there, Boyer and the shop parted ways.

Boyer decided to stay in the U.S but head East. A $45 train fare would get him to Chicago, Omaha or St. Louis. He picked the latter city, thinking it to be the farthest away. After his arrival there in 1869 he worked at several different jobs. He worked at the Fulton Iron Works for a year or so, took a job in Leavenworth for a while and then returned to St. Louis to work for Victor Sewing Machine Company. Soon he left Victor to join an inventor who was building a new type of sewing machine. When that company went out of business, he joined up with a fellow named Frederick Swaine and became part owner of Boyer & Swaine, a machine shop located at 420 Broadway. There they began producing bottle molds for the casting of milk bottles, beer bottles, pill bottles and the like. The partnership didn't last long and after a year or so, Boyer bought out Swaine. Soon, Boyer had set up his operation in a shop at 244 Dickson. (Dickson was formerly known as Bates until 1881.)

These various jobs occupied about nine years and it was around 1878 when Boyer settled into this shop. Boyer had met and married Clara Ann Libby in 1874 and by 1880 the couple had three children. They would eventually have eight.

One of the roadblocks in the bottle mold business was chipping out the waste from a mold. In 1882, Joe Boyer submitted a patent application for a hand-held chipping tool powered with compressed air. This would evolve into the pneumatic hammer that was used to drive and finish rivets. Where it formerly took two highly skilled boilermakers with heavy sledge hammers three minutes to drive and head a rivet, now a single worker with a pneumatic hammer could do the job in five seconds. Boyer had a number of other inventions but this one, with subsequent improvements, was his most important.

Boyer didn't immediately seek to sell his pneumatic hammer commercially. An article in the July 26, 1917, issue of American Machinist details the developments that eventually led to its commercial success and sales via the Chicago Pneumatic Tool Company. This success came only after patent lawsuits and other struggles with The American Pnuematic Tool Company that had a competing product on the market. Along the way, Boyer had the good fortune to meet and employ an outstanding patent lawyer, Edward Rector. Rector would remain a close partner of Boyer through the years.

By 1900, Boyer had relocated along with his machine shop to Detroit. In late 1901, newspaper articles announced the consolidation of the pneumatic tool industry including Boyer Machine Company into Chicago Pneumatic Tool. Boyer would remain a Detroit resident until his death in 1930.

(TO BE CONTINUED)