William S. Burroughs

and Family

The Early Years

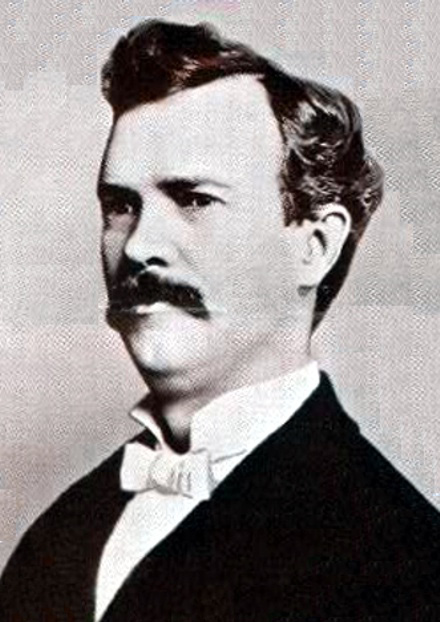

William Seward Burroughs – The Biographies.

In 1912, the Burroughs Adding Machine Company published a 190 page book

titled “The Book of the Burroughs.” It's accessible on-line, currently, via Google

Books and must have been a great aid to Burroughs sales force. There are

examples of various uses for the adding machine, testimonials from satisfied

users and examples of a few of the 84 models that had been created in the

previous twenty years.

Midway through the book, there is a brief

history of the company and a biography of William Seward Burroughs. The

biography states, in part:

William Seward Burroughs was born in Rochester, N. Y., January 28, 1857. He was, of course, a mechanical genius – one of the greatest the world has ever known – and this genius was born with him just as much as his eyes and his ears. Nevertheless, he never realized this until after he was twenty-five years old, when, at his father’s desire, he entered a bank in Auburn, N. Y.

… From Auburn, Burroughs went directly to St. Louis, and secured employment in a machine-shop where a great deal of miscellaneous work was done.

There are a number of other biographies of Burroughs and most settle on the

period of employment at the Auburn bank as seven years while at least one

claims ten years. A little bit of obvious fact checking for the Book of the

Burroughs at this point has Burroughs working at the bank in Auburn until

(1857 + 25 + 7 =) 1889 which turns out to be some five years after he filed

his patent application on his adding machine after spending a number of

years in St. Louis.

A good deal of creativity appears to have been employed to deal with some of

the dates in these biographies. For example, Burroughs’ obituary notice

moved his birth date back to 1851! More recently, an article in the IEEE’s

Annals of the History of Computing dealt with some of these discrepancies in

a footnote, identifying references to Burroughs’ year of birth as 1851, 55

or 57 but without definite resolution.

Another issue with all of the biographies is the omission of the fact that

most of Burroughs' childhood development and education took place in Michigan,

not New York!

William Seward Burroughs – The Real Story

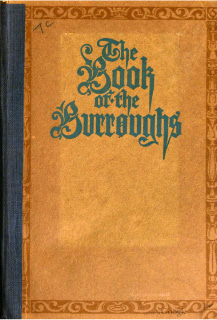

Burroughs' paternal grandfather,

James C. Burroughs, was born in New York in 1802. He married Rosette E.

Tuthill in Seneca Falls on January 11, 1836. (This was most likely a second

marriage for James.) James and Rosette joined the national migration to the

open spaces of the west, making it as far as Kent county, Michigan, before

settling in on a farm in Vergennes Township in the early 1840s. He purchased

about 75 acres of land along the Flat River there in 1848, two and a half

miles north of the town of Lowell, about fifteen miles east of Grand Rapids.

A significant portion of the settlers in this area came from the "finger

lakes" area of New York around Seneca Falls, Auburn and other towns in

Cayuga and Seneca counties.

Farming appears to have been generous to the Burroughs family as James is listed in the 1860 census having $8,500 in personal wealth in addition to his real estate. In May of 1865, James was one of nine members of the community to organize a national bank in Lowell. Unfortunately, he passed away in October of that year at age 64. Rosetta continued as a stockholder of the bank through at least 1881 but the bank ultimately suffered problems in 1885 and closed its doors in 1888.

If you were to visit the Lowell area, today, there are still a few reminders of the Burroughs family. Burroughs Street bisects the old James Burroughs farm. The building constructed to house the national bank is still standing downtown. And, James C. Burroughs is buried in the front row of Fox's cemetery adjacent to other founding fathers of the Vergennes community.

Edmund Burroughs, a son of

James C., was born in New York in 1826. (Edmund sometimes shows up in public

records under the name Edward, Edwin or even Ebon.) The 1860 census finds

Edmund and his wife, Ellen, living in Rochester, N.Y. with two sons: Charles

E., age 8, and William, age 3. William is, of course, our subject of

interest, William Seward Burroughs. The Burroughs also have a daughter,

Anna, who is 5 years old. Edmund’s occupation is listed as a mechanic, the

family has an Irish servant girl in residence and Edmund claims personal

property worth $2,000. Since the typical factory wage of the time was about

a dollar a day, the Burroughs family was definitely upper middle-class at

this time.

In late 1860, Edmund Burroughs and family moved to

Lowell, Michigan, a short distance to the south of James and Rosette's farm. Shortly thereafter, a fourth child, James, was born. Some

67 years later, James would sift through the family records for a newspaper

reporter and confirm that they had moved to Lowell in 1860 and then moved to

Auburn, NY, in October of 1871 .

The years in Lowell would have great influence on William. His older brother Charles, recalled that William spent a great deal of time out in the woodshed where his father's shop was located. He showed an early talent for tool use and like his father, was always building something. He also gave evidence of persistence and resistance against opposition. One thing he did not have was a talent for physical activities. Charles described William as hopelessly outdistanced in any boyhood activities rquiring strength or endurance.

In the fall of 1871, as William was preparing to enter High School, the family moved back to the finger lakes area of New York, settling this time in Auburn. What drew the family to Auburn is not clear. Perhaps relatives on one side or the other?

William's younger brother, James, remained in Auburn the rest of his

life earning his living as a printer for many years before venturing into

the emerging automobile business. James’ recollection of events and dates is

very important because he offers a much different source for

Burroughs’ inspiration to develop the adding machine than is generally

stated:

When William Seward Burroughs in the winter of 1871-72 decided he'd like to go to the old Genesee street No. 2 School in Auburn to listen to a talk on "Mathematical Short Cuts" he little dreamed that he was to be fired with an idea that would revolutionize clerical office practice throughout the world. He merely expected some interesting tips that might help him with his arithmetic. But the train of thought created in the boy's mind by the speaker, whose name has been forgotten, led the lad through sickness, financial wreck and discouragement to the end of the rainbow to find success.

William that night in the old Auburn school house conceived the idea of an adding machine. After a half day of experimenting, he exclaimed: “When I get to be a man I will make an adding machine that will amount to something in the world.

“Willie,” as he was known in the family, would have been fourteen at the

time and younger brother James, ten. Willie’s enthusiasm doubtless made a

strong impression on his younger brother. James also lets us in on the fact

that Willie left school after two years at Auburn High. This fact was

probably not something the Burroughs Adding Machine Company wanted widely

known. It also causes a lot of problems with dates in the Burroughs

biographies.

We know from the Auburn city directories that Burroughs worked

at the Auburn post office and also as a planer in a lumber yard. The

directories never list him as employed at a bank. Once again, brother James

comes to our rescue:

His first job was in the post office, then located at 7 Exchange Street. From there he went to the Cayuga County National Bank, under A. L. Palmer, cashier, where he became discount clerk and broke down from overwork when the bank undertook to discount, as individual items, the notes of the big D. M. Osborne & Co.

... After a long and serious Illness, William went into manufacturing on a small scale and lost all he had. Undaunted, he removed to St. Louis, Mo., in 1881.

James should be a very reliable witness on this account since he was also

working downtown, near the Cayuga County National Bank, in his own printing

business beginning about 1877. A(lanson). L. Palmer was indeed the Cashier at the bank,

being promoted to that job from teller, in 1873. D.M. Osborne was a major local manufacturing and publishing concern. I only

cast a skeptical eye on that date for W. S. Burroughs’ move to St. Louis.

A check of the St. Louis 1880 census records finds William Burroughs

and his wife, Ida, living at 835 South Seventh Street. And, Burroughs’

father, Edmund, is living there with them. (Edmund gets counted twice in

this census since he is also enumerated back in Auburn!) Precisely when W.

S. Burroughs and his father moved to St. Louis is an open question. The

Auburn city directories continue to list the senior Burroughs as a machinist

through at least 1884. However, the 1878 St. Louis city directory is the

first to list an Edward Burroughs, a pattern maker who boards at the Girard

House. The 1880 St. Louis directory shows Edmund Burroughs as a mechanic

operating his business at 114 N. 7th St and residing at 703 Chestnut. He is

also listed under the heading of Machine Shops. There is not much

doubt that W.S. was firmly situated in St. Louis by 1880. The original

U.S. census was taken in June but was rejected and a second enumeration was

conducted in November. In that second count, we again find Edmund boarding with W.S. and

Ida but now there is a fifteen year old black servant girl also in the home.

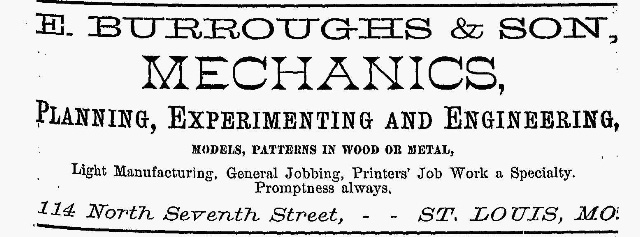

The 1881 Missouri

State Gazetteer and Business Directory includes this advertisement for the

Burroughs operation:

One of the earliest of the Burroughs biographies was published in 1899 in a monumental four volume work titled Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis. The editors get some dates wrong but are very specific in describing Burroughs’ work during his early years in the city:

In 1881 he came to St. Louis, and for a short time thereafter worked in his father’s model shop on Pine Street. Later he worked for the Future Great Manufacturing Company, on Morgan Street, and still later for Hall & Brown, on Broadway, in the manufacture of wood-working machinery. His experience with his father and these two firms, covering in all a period of about three years, constituted his entire training in practical mechanics. He had, however, a genius for theoretical mechanics, and his experience in his father’s shop brought him into contact with many inventors.

Obviously, Edmund and his son, William, had a close relationship. It’s worth

learning a bit more about the senior Burroughs. Some biographers note that

Edmund was a mechanic and an inventor. At least one notes that Edmund held a

patent on a railroad jack. Edmund’s pursuit of his inventions appears to

have taken him away from the family for long periods. The several years that

he spent in St. Louis while Ellen, Anna and James remained in Auburn are one

example. Also, the 1870 census report from Vergennes Township in Michigan

shows only Ellen and the three youngest children along with Rosetta. Edmund

is somewhere else. It is probably worth noting that although “Edmund

Burroughs” is certainly not a unique name, the Detroit city directory for

1862 shows an Edmund Burroughs working as a mechanic for the Michigan

Central Railroad. In the summer of 1863, Edmund did register for the draft

listing his residence as Lowell.

Edmund may have been planning to

utilize water power in his Lowell shop. He applied for and was granted

permission in the spring of 1867 from the Michigan Legislature to build a

dam on the Flat River in section 35 of Vergennes township. Living along the Flat

did cause Edmund to develop a

fondness for the water. During 1867, he took off on a paddling expedition,

exploring some of the inland waters of Michigan. He describes the physical

and mental benefits of the trip in an 1890 newspaper interview :

At that time I had a young college student with me. He was nearly dead from overstudy and confinement when we started. We traversed the principal inland waterways of the state of Michigan, and when we returned home the parents of that youth hardly knew him, so much improved was he in health and spirits.

It is worth noting, of course, that the Burroughs’ oldest son, Charles, was

eighteen at the time and may well have been the student Edmund described.

Charles would go on to a career in New York City. Anna would become a

successful music teacher in Auburn. James, as previously mentioned, would

enter the printing trade in Auburn.

All the biographical accounts

agree that William Seward Burroughs’ suffered from a “long and serious illness”

and that the illness was

Tuberculosis. Doctors recommended leaving the severe cold of Auburn

winters for a milder climate. His move to St. Louis and the initial

partnership with his father there was the result. The desire to build an

adding machine that he had expressed earlier would now become an obsession.

If the climate in St. Louis was good for Burroughs’ tuberculosis, it was

bad for precise drawing. Burroughs found that the high humidity caused

shrinkage and expansion in his drawings. He solved this problem by

scratching his concepts onto metal plates. By late 1884, he would have a

working model of his adding machine and file an application for a patent in

1885. Along the way he would meet several people who would become key to the

commercial success of his invention.

(continue)